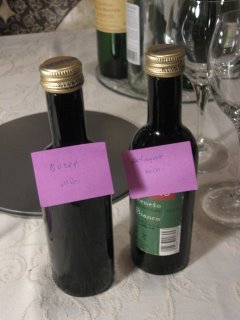

My experiment in storing opened wine: Etchart Privado Cafayate & Carte D'Or Buzet 2003

The other night I opened a couple of low-end Cabernets. The first one was a Buzet blend from 2003. It was a disappointingly hot cuvée from an otherwise reliable co-operative. I didn't drink too much of it before I turned to open the other Cabernet, also from 2003. This one was Etchart's Cafayate Cab Sauv. It was better -- though not exactly supple either -- but my dinner was practically finished by that point.

And so, as a solo drinker, I faced a major storage issue: the better part of each of the two bottles I had opened for myself remained there in front of me, waiting for another opportunity to be drunk.

I keep several mini bottles of varying sizes specifically for leftover wine purposes. If you've read this blog before you know that I routinely minimize the amount of air and then chill until next serving, usually in following 48 hours (at which point I usually comment on the wine's development/degradation). But I've never attempted to formally prove why this rebottling process is worth the effort. Why bother transferring a half-full bottle of wine at all? Well, here is what I did and what I found out...

I filled a mini bottle to the brim with the Buzet, tightly screwcapped the lid and refrigerated it. I then repeated these steps for the Cafayate. That left roughly 1/3 of the wine in the original bottles. I re-stoppered them both with their respective corks and left them to sit at room temperature -- 18 degrees Celsius. And I waited three days before returning to them.

A bit of background and rationale for you: The effects of oxidation of wine -- basically wine tasting flat -- occurs through a natural process that is stimulated once the bottle is uncorked. But there are many people who say that the pouring of wine from half-full bottles (and into mini bottles) dissolves just as much oxygen in the wine as leaving the wine in a bottle that features a vast expanse of air. (My own educated guess from experience was that the presence of air over time during storage would be a greater oxidizing force than the momentary act of pouring into a mini bottle.)

To this experiment, I added a second variable of storage temperature. I wanted to investigate this because I always chill wine remainders rather than keep them at cellar temperature or room temperature. Yet I rarely or never see restaurants serve red wine by the glass in such a manner, and I have heard that oxidation is slowed at lower temperatures.

Days later, the wines are reopened and tasted. The results were conclusive. The methods of storing wine made for a very detectable difference in a blind taste test. Not only that, but the wines that were stored using my typical method tasted better than the other stored wines. I found this in a blind experiment comparing the Buzet samples and a second participant also found this when comparing the Cafayates blind during a second round. (After my first round, I separated out the two Buzet samples by deduction: since I had isolated and revealed to myself the two Cayafate samples -- which had tasted so radically different that my initial hypothesis was that one was a Buzet and the other was a Cafayate -- I was able to perform a second round of blind tasting for the Buzet. See complete notes below.)

CONCLUSION, FUTURE RESEARCH, AND MY ROUGH TASTING NOTES

Unfortunately, with this experiment, I cannot say whether it was storage temperature or presence of air that had a greater effect on the stored wine. Likely these variables are intertwined. Regardless, my storage method is better than doing the standard recorking, which is pretty much doing nothing at all.

This experiment looked at oxidation in a somewhat limited sense. It was more or less assumed that the more oxidized a wine became, the less palatable it would be. This should not be taken as a constant rule. In choosing Cabernets and a period of three days, I suspected that some elements of the wine might be more palatable, and I definitely think that the Etchart Privado Cabernet Sauvignon Cafayate 2003 was more fully developed three days after opening than immediately out of the bottle. This adds some interesting "reverse psychology" when creating storage conditions for your leftover wine, and certainly goes against Émile Peynaud's theory that aeration of opened wine is indefensible, something I consider even easier disprove than perceived rates of oxidation. Nevertheless, the Cafayate could've been drinking beautifully after one day or two days -- I cannot speculate on that based on this experiment.

Here are my complete notes:

MINI BOTTLE, CAFAYATE SAMPLE: Lovely bouquet of minerals and spice (Ed: I totally pegged this for French Cabernet -- and a good one at that -- when tasting it blind. Again this raises questions about whether the a little oxidation/aeration isn't such a bad thing).

ORIGINAL BOTTLE, CAFAYATE SAMPLE: Heaps of spice. Obvious oak and vanilla. (Ed: This tasted too round and flabby -- as I often expect oaked New World wine to be after a couple of days. That said, it was surprising to me that it tasted as good as it did considering it was so full of air and at room temperature for so long. Credit to Etchart for an outstanding value Cabernet.)

MINI BOTTLE, BUZET SAMPLE: too hot, quite unpalatable

ORIGINAL BOTTLE, BUZET SAMPLE: totally rounded, thoroughly tasteless

(Ed: These two Buzets were harder to differentiate than the Cafayates, I think because of the fact that this wine, even in its optimum condition, was hot, and rather nasty. The original bottle Buzet sample simply stood out as the nastiest of the nasty, and having seen how the original bottle Cafayate sample played out in round one of my tasting, I was fairly sure how to label these two Buzet samples.)

4 comments:

I think anonymous is over reacting a bit to your experiment. . .

Nice work but it would be even more interesting if you compared the Vacuvin and Private Preserve to the half-bottle method.

Also, pouring wine into the bottle puts it in contact with air but doesn't really oxidize it because the contact period is too short. Oxidation is a chemical reaction that takes a little more time than a few seconds.

Steve,

You've got a good idea there. Perhaps with more feedback, I will redo this test. (I'm starting to wish that I hadn't introduced the temperature differences to the different container sizes -- I can't rightly isolate their effects. I will have to get back at it again soon.

Your pouring comment though -- it sounds like common sense but I was thinking of PhD Jamie Goode's writing on how the dissolving of oxygen in wine is governed by one-time events in which the amount of oxygen present is not significant, i.e. pouring would introduce enough oxygen to do the same thing that the cavernous bottle storage would do, as in this article (especially the inset at bottom). Hope I'm not losing the thread like our anonymous commenter, but what Jamie said, along with ideas of Émile Peynaud, were my main reasons for exploring this.

Yes, I'm no scientist!

I'm a big fan of Jamie's but the comments in the inset made the whole thing sound futile. Perhaps it is!

People also in the past used marbles that they added to partially full wine bottles to "force oxygen" out. Seems the same as using mini-bottles--which gets rid of the "head space".

Problem is, you gotta clean the marbles and mini-bottles and you gotta store them!

www.ultrawinesaver.com

I am the inventor and owner of a hand held device that gently puts a layer of Argon gas into your wine. In my opinion, keeping a hand held device in your cupboard is preferable to keeping and cleaning 50 mini-bottles every week.

Check out our website, I think many of you would be impressed.

Post a Comment